This is a re-post of an article I wrote and published here last March. I’ve done a lot of research and read many books on farming, but researching for this post was probably one of the more disturbing things I’ve done. But the reality is everybody needs to read it and educate themselves on the subject.

This is the post that nobody is going to like. Nobody wants to read. Nobody wants to even hear about it. But the truth is that most people aren’t aware of it, so I’m going to tell you, like it or not.

Chickens are big business. There are far more of them in the world than any other bird – approximately 26 billion in 2008 (don’t ask me who counted them, I certainly didn’t….) They are a large and important source of protein in human diets across the world, both for the meat and for the eggs.

People also like eating both; they are popular foods. And in order to satisfy the demand for cheap, reliable sources of both eggs and chicken, they are mass-produced all over the world.

Over the past several generations, the traditional farmer has all but disappeared to be replaced by “factory farms”. This term applies to all forms of animals that we eat. Chickens; both egg and meat chickens, pigs, cows and fish. Between 1955 and 1975 flock size in a typical egg factory rose from twenty thousand to eighty thousand birds per house as production learned to stuff and stack the cages. Just as the cage brought a Brave New World for laying chickens, it brought the end of an era for family farmers. The automation of feeding, collecting, and removing wastes made human labor and thousands of family egg farms obsolete. And it did so quietly and quickly. In 1967, 44 percent of commercial layers were in cages; by 1978, 90 percent were in cages

A natural chicken, wandering around in a flock outside with good predator protection and a rooster to protect them, might live to be 10 or 14 years old. In the modern egg factory hens only have a lifespan of around a year and a half. Generations ago, eating chickens was a luxury for people. Most farmers kept their chickens for the eggs and only ate the young roosters or the older hens that stopped laying productively.

The average egg on your grocery store shelf is anywhere from one month to six months old. This is not normally the fault of the grocer, but of the egg producers, who keep them in cold storage until they are needed.

If you buy just regular eggs at your grocery store – not labeled “organic”, or “free-range” — they come from a factory farm that looks something like this.

They are mostly kept in small cages, and cannot move around or stretch their wings fully. 70% of egg-layers are either in crowded barns or cages. A normal and legal cage is 20 inches by 20 inches, and contains 4 or 5 birds – sometimes up to 10 birds per cage;

Cages are made from wire, to allow droppings to go through the cage, and they are sloped so that the eggs roll out for collection;

On average, a layer produces 340 eggs per year;

The cages are stacked on top of each other in sheds, and many contain tens of thousands of chickens. 70% of battery layers are in sheds containing 20,000 to 100,000 birds, and they are incredibly noisy. Hens are often over-fed and given drugs and supplements, as with meat chicken.

And if you think you’re doing yourself — or the chickens a favor by buying “certified organic”, “Free-Range”, “Cage-Free”, or “Free-Roaming” eggs, they probably are coming from a factory farm that looks something like this:

Black Eagle Farm, a “cage-free” operation in Virginia, houses 48,000 hens. Platforms are designed to cram as many hens as possible into the building. This is a typical large-scale commercial operation being advertised as “animal friendly.”

All of this discussion about the realities of organic egg production got me wondering about the various labels on my egg carton. Here are definitions of some of the most common, courtesy of the Humane Society:

Certified Organic: The birds are uncaged inside barns or warehouses, and are required to have outdoor access, but the amount, duration, and quality of outdoor access is undefined. They are fed an organic, all-vegetarian diet free of antibiotics and pesticides, as required by the USDA’s National Organic Program. Beak cutting and forced molting through starvation are permitted. Compliance is verified through third-party auditing.

Free-Range: While the USDA has defined the meaning of “free-range” for some poultry products, there are no standards in “free-range” egg production. Typically, free-range hens are uncaged inside barns or warehouses and have some degree of outdoor access, but there are no requirements for the amount, duration or quality of outdoor access. Since they are not caged, they can engage in many natural behaviors such as nesting and foraging. There are no restrictions regarding what the birds can be fed. Beak cutting and forced molting through starvation are permitted. There is no third-party auditing.

Cage-Free: As the term implies, hens laying eggs labeled as “cage-free” are uncaged inside barns or warehouses, but they generally do not have access to the outdoors. They can engage in many of their natural behaviors such as walking, nesting and spreading their wings. Beak cutting is permitted. There is no third-party auditing.

Free-Roaming: Also known as “free-range,” the USDA has defined this claim for some poultry products, but there are no standards in “free-roaming” egg production. This essentially means the hens are cage-free. There is no third-party auditing.

Male chicks, who are of no value to the egg industry, are immediately killed. They are either tossed into garbage bags, left to suffocate or to be crushed, or are macerated in high-speed grinders.

Dumpsters full of male chicks. They are normally thrown in alive and just left to die of suffocation or starvation.

For the female chicks, after birth they are kept in grow out buildings for about 20 weeks. They are often kept in dark except at feeding times.

I am going to quote directly here from a website I found by Wesleyan.edu by an anonymous writer that visits to a Connecticut factory chicken egg farm:

“Inside the Battery Shed”

By Anonymous

The first visit…

“We went in the other night, through the manure pit door. We had to step over a dead hen in the doorway. It was Shed 7 based on our counting. We quickly changed our clothes and boots in order to maintain biosecurity. (Such measures were necessary because the stress from living in overcrowded, dirty conditions impairs the immune systems of battery hens making them very susceptible to disease. Furthermore, the overcrowding of the hens encourages the spread of contagious diseases, so it is important that every one who enters the shed be free of contaminants).Immediately I was surprised to see a number of hens resting atop the huge piles of shit. A part of me was glad for them, those free from cages, but also sad. I knew that they would soon die of thirst. There is no water to drink in the manure pit. Before entering I thought we would be heading straight up top, in a hurry to see the infamous battery cages; I was struck by how much there was to see below. Live hens, dead hens, and demolished hens. There was at least one bird smashed to smithereens with head off, legs off, feathers lightly spread. I cannot imagine what could have caused such violent destruction, but I hope she was dead before the deconstruction of her body. We tried to record the cruelty, the haunting atmosphere. I took many photos, but I know that only a visit can portray accurately the battery cage shed.

The Manure Pit

We climbed the ladder up, getting dust on ourselves, and there we were staring at the battery cages. There were cages upon cages, upon cages, upon cages. Stacked four high with six rows with cages on either side of a row. Later we counted 381 cages in a length, making 18,288 cages per shed. The average seemed to be five hens per cage, making 91,440 hens per shed. 13 sheds means over one million hens at the farm. The cages were measured roughly 16 inches wide, 21 inches deep and 18 inches high. 2.33 ft2 for the hens to share. No room to flap wings.

The hens in cages this Connecticut Factory Egg Farm

I was shocked by the amount of defeathering. Some of these birds were naked, with highly irritated skin. The feathers they did have were hard and brittle. So dry, but everything in there was. (At the time I had never held a healthy chicken. I have since had the opportunity; the difference is startling.)

With the crowded condition, the chickens have nothing left to do but pick at each other, often to death.

The hens can sense tension, so we took every effort to remain calm. They did not react to flash photography, or mind me measuring their cages. We walked the whole length of the massive shed. At the front we came to all the egg collecting machinery. I wondered, how much human involvement is there?

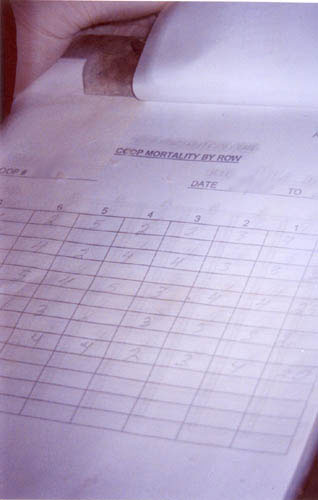

At the front we found a mortality chart: 70 hens died in that shed alone that day. Multiply this by 13 sheds on the farm. That is a lot for one farm, but with over a million there, what are a few hundred dead ones to them? We continued observing and investigating, and eventually made our way back to the rear of the shed. There in a corner we found a barrel half full of dead hens.

The Coop Mortality Chart. Only 70 that day. The mortality rate at these factory farms is horrifying.

Surrounded by all this death, suffering, and blatant cruelty you would expect, you would hope one would be in tears, and by the end my companion was, but for myself those feeling were forcibly put aside. The conditions were so horrible, how can one be compassionate and walk around in there? Tears come more easily now in reflection than while inside. It is just too overwhelming. With almost a hundred thousand hens in that shed alone it is hard to realize their individuality. I got the feeling inside that I wanted to liberate them all, every last hen. For most of the birds it is too late. Their feathers fell off long ago, and have never known a freedom they could even dream of. The struggle is more personal than ever. I will keep going back, keep investigating, keep liberating until battery cages are banned, an antiquated horror.”

One week later…

“We went in again the other night, same shed, same routine. I thought that since I had done it once already it would be nothing, I was prepared. I could not have imagined the conditions would be so much worse in just one week. The half a barrel of dead hens had exploded to three full ones next to a huge pile of dead hens. There were as many as six or seven dead hens lying in one aisle. I could not believe there were even more: a few milk crates full and more barrels at the far end. Dead hens were left in cages too. I was shocked by it all. And the live hens had no feathers at all. How could it have gotten so much worse?

Barrels full of dead chickens. They die from mutilation, starvation, respiratory distress from the air conditions in the sheds, and a multitude of diseases

There were flies swarming around us at times, and rats, dead and alive. With so many dead hens around, flies and rats are not too surprising, neither is disease. It is as if the farm management was mocking our careful efforts to for biosecurity with their complete disregard for keeping out potential contagions. The time we spent in there went by so quickly as we tried to record the horrible conditions. We spent so little time paying attention to the hens in cages because everything else was so bad. I cannot stress enough how much worse everything was than in my last entry.

We helped a hen free herself from being stuck in the bars her cage, allowing her access for food and water again. Helping that one hen helps me deal with the lingering reek of chicken shit that the laundry could not eliminate.”

One and one half weeks later…

“Last night we went back to the farm, the factory farm. We headed straight to “Shed 7,” again through the manure pits. Immediately we were hit by the smell and saw the familiar piles of shit. Then my friend looked up and exclaimed, “The chickens are all gone.” There were no more chickens. To be exact, there were still some around on the manure. I went over to one and she just sat in the corner near a pile of snow as I approached. I picked her up and realized why she had not moved. She was sitting on an egg. After all that time in a cage in which her eggs would roll away from her she still wanted to sit on her laid egg.

We then climbed the ladder upstairs. At once I was glad I had a dust mask, as there was so much ammonia it was difficult to breathe. We moved quickly, but stopped many times to photograph rotting hens in cages. We recorded as many as we could, but eventually we had to move on; the ammonia was too strong. The hens that remained decomposing in the cages were in a state I was hardly prepared for. Thinking of it now brings back the indescribable smell of the sheds. We made haste back down. I never thought I would find the air in a manure pit so refreshing.

Dead hens left to rot in their cages

We went to another shed. The chickens were in better shape here than in “Shed 7,” but the cages were so full: up to ten in a cage! The hens were already suffering from feather loss. Ten hens will not last long in a cage so small. The nature of the cycle became clear to me: fill the cages with ten hens and then once half of them have died empty the shed and start over again.

We then went to another shed. This shed was further along in the cycle. Greater numbers were dying each day according to the mortality charts. There was more feather loss. Dead hens in cages, even an extremely decomposed hen in a cage being sat upon by the remaining hens. It was all so draining; it wears on you. A couple of hours inside was as much as we could handle, and we left on edge. I cannot imagine what it takes to work there, or rather what you would have to lose.

I left eager to share my experience, to share my newfound knowledge. I had no comprehension of what the conditions for hens were like before our investigation. Even now, I still cannot begin to imagine what life would be like being spent entirely in a battery cage.”

This was a very difficult post for me to write. Researching for it was heartbreaking. But if people don’t educate themselves to the horrors of factory farming it will continue.

Move a muscle. Change a thought. Write a letter. Educate yourself. Get some of your own chickens.

From what I have learned by both attending the Young Farmer’s Conference in December of 2010 and researching for this post, the only way you can be certain that the eggs you buy have been raised in a humane, loving environment where they truly get to free-range on grass and bugs as nature intended is to either buy your eggs locally from a farmer, or buy eggs with an “Animal Welfare Approved” stamp on them. You can click on the link to them here and find a listing of local suppliers in your area. After taking their seminar at the Young Farmer’s Conference, I would qualify right now for the guidelines they have for getting the Animal Welfare Approved certification. Perhaps when my new chicken coop and goat barn are complete I will apply.

Anybody that lives near me can see my chickens and goats roaming around the yard freely eating food as God intended them to. I have never had a chicken with a disease or health problem. I have never had a problem with feather-picking, as this is an indication of overcrowding and boredom. I am proud that I raise my chickens in a way that makes them happy. They are happy to see me and run to see me when I come around the corner. They make me happy.

So if you’re driving down the road and see a sign for fresh eggs, by all means stop and buy them. I can guarantee they were raised in better conditions than the chickens that provided the eggs at the grocery store were, and you’ll be helping a struggling local farmer at the same time.

This post was awful. I’m going to end it here with some of my happy chicken photos.

My chickens free-ranging in the woods for tasty things to eat last week.

Free ranging around the yard.

One of my favorite roosters ever. The wonderful Mr. Pocket. What a character in a pint-sized package.

That is both horrific and enlightening. I will definitely be driving the few extra miles to the local farmer’s market to buy my chicken and eggs. Thanks for sharing.

I was more than happy to find this insetner-tite.I wanted to thanks to your time for this wonderful learn!! I positively enjoying each little bit of it and I’ve you bookmarked to check out new stuff you blog post.